Thoughts from the Director of the Huck Institutes

November 2023

As I begin writing this month, a cold wind whips at my office window and large snowflakes chase each other around the plaza outside Eisenhower Auditorium. It’s gray outside, and the change of seasons feels heavy and ominous, casting shadows on my frame of mind.

In moments like these, I like to remind myself of the purpose of our work – to re-energize my mind and shake off the chill of the encroaching Winter. Thinking back to last month's column on impact (see October's post below), I recall that a handful of you took the time to respond to the questions I posed.

I’m thankful for those answers, which are already beginning to refine my own thinking about what research impact really means. And I realize how important it is for me to hear more.

For those reading this column who have not already done so, I would deeply appreciate hearing about the impact you are making with your research, and reading your thoughts on how we should be measuring our impact at the Huck (please do so here). It's truly important, because impact lies at the core of why Penn State and the Huck Institutes exist.

While writing this column, emails flutter into my inbox from all corners of the university. As usual, I receive a continuous stream of messages about our scientists publishing high-impact papers that address some of the greatest challenges facing humanity: new discoveries for purifying synthetic antibodies (Yong Wang), deeper understanding about male fertility (Kateryna Makova and Wansheng Liu), new diagnostics for debilitating disease (Dipanjan Pan), and expanding our understanding of autism (Santhosh Girirajan) are just a few recent examples.

New, multimillion dollar grant proposals crafted by large multidisciplinary/multi-institutional teams depart Penn State through the ether, flying off to do battle for funding. And notices of allowance for funded grants fly back through these same channels, bringing exhausted smiles to the faces of busy researchers.

Taking a break from writing, I head off to meetings with some of our best and brightest scientists, who work in large interdisciplinary teams to attack big challenges and set the stage for even more impact. Group innovation abounds, across regenerative engineering, neuroscience, rehabilitation sciences, pollinator health, cell biology, cancer, microbiome, plant and animal sciences, and much more.

I get updates from faculty in our Centers and Institutes who huddle together, imagining new ways to improve the health of the environment and help human beings thrive. I walk past our shared instrumentation facilities, encountering the bustle of skilled scientists and students orchestrating the activities of some of the most powerful analytical equipment ever invented.

And the data! Terabytes race through wires and land in analytical software platforms, to be tended and interrogated by data scientists, modelers, statisticians and biologist to reveal their secrets, all in hopes of gleaning new insights into the functions that support life.

Circling back to the quiet administrative hum of my office, I am surrounded by the skilled staff of a large and very busy research institute. These are the people who keep resources flowing to our units like a heart pumping oxygen to the body. Accounts being managed, authorizations approved, new hires, events and meetings, creative works and storytelling, renovations and reorganization of the research machine.

Budget balances are nervously watched as decisions are made to purchase even more powerful equipment, hire new faculty and staff, seed new research collaborations and support advanced training of our graduate students. Each decision is a carefully thought-out and optimistic bet on future impact.

Back at my computer, I find myself in a decidedly different frame of mind. Eyes closed to block out the shadows brought on by the gray and cold outside, I pause to feel the power of this institution and the important role it plays. And I realize how grateful I am to be surrounded by such a talented and productive group of faculty, staff and students.

The cold, gray wind again bangs at my window, challenging these happy thoughts. But it is rebuffed.

In my last Troy’s Take of 2023, I want to express my deep gratitude for your hard work on behalf of team Huck and Penn State. During the holiday break, I hope you have time to relax and reflect on the powerful force for good Penn State plays in the world. And I hope, like it does for me, this brings you deep satisfaction, renewed energy and optimism in 2024. We are part of the solution; We Are - Penn State.

-Troy

Past Messages from Troy Ott

2023

Last month, I discussed change, and its sibling, opportunity. This month, I want to reflect on impact – specifically as it relates to Penn State research. As a Land-Grant, Space-Grant, Sun-Grant and Sea-Grant university (one of only two in the nation to be designated as all four), Penn State is formally, institutionally charged and committed to making an impact in just about every human endeavor. For this reason, we spend significant time and energy striving for impact and telling that story to the world.

But what I have been grappling with is the question of how we measure that impact in research and scholarly activity.

One method, of course, is about dollars. Research expenditures affects how we are ranked. “What was our research expenditure last year?” is a perennial question in any R1, top-tier research university like ours. And, in recent comments by the interim Senior Vice President for Research, Andrew Read, to the University Research Council, I learned that Penn State research expenditure numbers for FY23 are looking very, very strong – we are increasing our impact.

So, we must be doing something right. The institutions that grant research funding aren’t just handing it out willy-nilly. It’s a very competitive process. In most funding mechanisms, only the top 10% or so of proposals receive funding, and in many the funding line is much lower. One large grant proposal Huck is assisting with, and is currently in review, is competing for only one award in the entire country. It does not get more competitive than that. So, ostensibly, the very fact that Penn State science was selected so many times to receive funding reflects that fact that we are asking for resources to do important, world-changing and impactful research.

And yes, money is important. Especially when we endeavor, as we do at Huck, to take on big, complex challenges in a truly interdisciplinary way. This approach requires more people, more space, more technology, and more basic material resources. All of these require greater financial commitments – just to be able start down the path of greater impact.

For these reasons, research expenditure is certainly a valid measure of research activity. The trickier question, though, is to understand exactly how much all that research and scholarly activity impacts real people in the real world in a positive way.

Our research output at Penn State is roughly 10,000 papers every year. And when you add in other types of scholarly activity, how can one possibly get their arms around all that work to really get a handle on what impact it makes?

Of course, communication teams from across Penn State work tirelessly to tell as many stories as they can, day in and day out. One day we may read about new, high-quality jobs right here in Pennsylvania, created by Penn State entrepreneurs. The next we may see a group of researchers using the arts to inspire the next generation of innovators to reach for the stars. Just a day later, we may learn how our scientists have gained whole new insights into cellular protein synthesis, which could lead to impacts we can’t even conceive of now.

It's a dizzying, never-ending flow of creative energy and passion. And it is not easy to quantify.

But what I am hungry for – and I know I’m not alone in this – is a deeper conversation about impact. One that is broader and more nuanced than the one we’re used to having. I’d like to better understand how others around this university are thinking about – and working toward – greater impact in their research and scholarship.

We may never be able to accurately balance the scales on the impact of the discovery of a new molecular mechanism against the inspiration and awe inspired by a perfectly performed sonata or ballet or piece of visual art against development of new more productive variety of a plant. How do we value discoveries of the workings of our galaxy gleaned from peering millions of light years across the universe against development of a new microscope that allows us to see life at the molecular scale or a new algorithm that more accurately models a living process?

I’m convinced that Jackie Robinson’s take on impact is closest to the mark – “Life is not important except in the impact in has on other lives.” I truly believe that we are closest to the mark when we measure impact one person at a time, one discovery, one great lecture, one performance, one kindness. An approach that puts our people at the center or our aspirations. Because there is one thing that I know for sure, when we do this, we have the best chance of having an impact.

So, this is my invitation to you—all of you who, like me, strive for greater impact in everything we do at Penn State. What does impact mean to you? How are you working on it? How do you think we can have more impact? I sincerely want to hear your thoughts.

You can send them in here. It will only take a few minutes. But there’s no telling what the impact of those few minutes might be.

-Troy

Of all Nature’s seasons, Fall is my favorite. Something about the cooling temperatures, the colors of the leaves transforming and the ripening, harvesting and storage of crops reminds me that our world is perpetually in flux.

This year, Fall heralds more change than usual here at the Huck, and across Penn State.

Most Pulse readers know by now that Huck Director Andrew Read was called up to Old Main this past summer to serve as Penn State’s interim senior vice president for research, upon the appointment of Lora Weiss to serve as director of CHIPS R&D at the U.S. Department of Commerce. This, in turn, led to my appointment as acting director of Huck. Additionally, this Fall has brought additional changes in leadership in two of our Intercollege Graduate Degree Programs and our Center for Root and Rhizosphere Biology. This fall we also thank Nina Jablonski as she steps away from her leadership in the Huck and is named the inaugural Atherton Professor.

Beyond these changes in leadership roles, Penn State finds itself amid significant changes in both structure and direction. President Neeli Bendapudi has implemented a new budget model in her first year, and has generated a new set of six goals to guide the university to greater impact in its tripartite mission in the face of both internal and external headwinds.

How will all these changes affect Huck? I can tell you that I feel deeply optimistic. In my eight years serving on the leadership team, I can honestly say that this organization is as strong as it has ever been. While handing over the proverbial keys to the kingdom, Andrew’s charge to me was to take us from great to greater, and to move fast. He asked me to evaluate everything we do with an eye towards greater impact. That’s what I now strive to do.

And so, in my first communication to our community in my new role, there’s one key message I wish to impart: change brings opportunity, and we are poised to capitalize on it!

All the changes going on within and around us present real opportunities to do more than we ever have before, at the very things we do best. Consider for a moment that the second goal set out in President Bendapudi’s new plan is to “Grow interdisciplinary Research Excellence.”

Sound familiar? This is the foundation on which Huck and all our sister research institutes at Penn State were built. And Andrew Read, in his new role as lead for this goal, is wasting no time getting to work on it.

This is a time when must be prepared to move quickly, to take advantage of emerging opportunities, and to drive and shape new ones. It’s time to reflect on our mission, and what we need to do to deliver on it in bigger and better ways. And yes, that’s a tall order. But just look at our track record.

Over the past year, Huck played a key role (along with faculty and our partners in SIRO) in submission of nearly $70M in research grant proposals. These are large, multi-PI, multi-institutional proposals – each one a “swing for the fences”- that is high risk but also high reward.

Just this month, we announced the first cohort of 16 teams to be awarded seed funding by the new Inter-Institutional Partnerships for Diversifying Research program. This is a Huck-led effort that, for the first time, engaged all seven of Penn State’s interdisciplinary research institutes in a common mission to partner with Minority Serving Institutions to foster yet another kind of change. One that is sorely needed.

And last week I finished touring the shared instrumentation facilities – an experience that left me impressed by the quality of the people and the technology they employ to support our research, teaching and training.

So, where might we find new opportunities? I for one see exciting possibilities for more translational research, more industry partnerships, and more big science focused on impact. With a new Dean in the College of Medicine, I see new opportunities for cross-campus research collaborations. I will not forget what we’re here to do – to enable the Penn State research community to collaborate in risky, exciting new ways with a mission to solve the biggest challenges facing humanity.

So yes, there are lots of changes afoot. And no, things are not going to stay the same. They never do. As we go through this transition together, let’s work collaboratively to ensure that we take this opportunity to let all our colors shine as vibrantly as they do in the Fall here in Happy Valley.

-Troy

Past Messages from Andrew Read:

2023

Sometimes life takes unexpected turns. As of July 1, four and a half years to the day after I became Huck Director, I will be Interim Senior Vice President for Research. No one is more surprised than me. But when the President asks…. and says she wants a fierce advocate for Penn State Research….and that she wants a research active scientist capable of thinking ‘we’ not ‘me’… well, here We Are.

Recently, when I asked a job candidate for questions, she asked what I am most afraid of in the new position (insightful question to ask a possible new boss). My amygdala empowered my mouth to talk about the things that can go wrong across $1bn of research activity. But the candidate looked unimpressed, and rightfully so. Thinking about it after, I realize my real fear is failing to grab the opportunity I have been given to help PSU make the most of all the opportunities that it has been given. It is incredible what has aligned right now, at this place, at this time.

First, the pandemic has made a lot of people open to re-thinking a lot of things.

Second, at Penn State, we have new leadership charged to be change-makers and with a hunger to do it. This means we have been delivered a once in-a-generation chance to align our incentive structures to our values, our aspirations, and our mission.

Third, the higher education sector faces so many important challenges from so many directions that we need now – right now – to envision the next generation Penn State. Status quo won’t work.

Fourth, Pennsylvania needs us, and not just because we educate so many Pennsylvanians. More than ever, the challenges of our age matter to our state: the aging population, rural health, agriculture in a changing climate.

And finally, geopolitical considerations are pushing our nation to open opportunities for scholarship and workforce development in areas we excel in, like superconductors, rare mineral capture and biotech. Those same political forces also open new opportunities for international collaboration where we already make serious impact, with enormous potential for more.

Research is key to seizing these opportunities. Students come to Penn State to be around our scholars because our scholars are shaping the rest of the century. A lot of the agility will have to come from the Research Institutes, like Huck, which can move fast, experiment, and even break things without sinking the ship.

While I am away from Huck, Troy Ott will be Acting Director. Troy was on Huck’s Exec team when I started at Huck, and over the last four and half years, we’ve worked closely together, so I know him well. I am confident Huck will be great hands. He is great at getting things done, even the hard stuff. He is also as ambitious and optimistic and demanding of Penn State Research as anyone I know. I urge the Huck community to be as supportive of Troy as you have been of me. Complaints, brickbats and excellent ideas: t.ott@psu.edu.

-Andrew

2022

Two work events from 2022 stick with me. One was Penn State’s first ever celebration of teaching, research and clinical faculty promotions. Non-tenure line faculty do so much for our research enterprise and our students, and University recognition of their success was long overdue. Huck collaborated with the Schreyer Institute for Teaching Excellence to host the event. I was proud we did it, and I hope we established an annual tradition.

The other event was our Board of Trustees visit. During the hour they were with us, a Trustee asked me about the income being generated by our cryo-electron microscope. The instrument cost roughly $10m, a purchase approved by the Board before my time as director. The microscope is revenue generating, but user fees are just a fraction of the return on investment (ROI). What then, he asked, was the ROI?

That’s an important question. Accountants often say that research costs a university more than it brings in. And if you just want to balance annual expenditure against annual research income, that’s probably true. But if you are interested in your university making a difference in the world, ROI calculations need to include what economists call externalities, costs and benefits that accrue elsewhere in the university and in society more broadly. Externalities are not easily internalized in ROI calculations on an instrument.

Fortunately, Huck’s visit with the Board included a number of inspiring voices that helped to bring some externalities into better focus.

Deb Kelly, for one. Recently elected President of the Microscopy Society of America, Deb came to Penn State because of the instrument. Her work on it has led to patents for early diagnostics for breast and ovarian cancer. Those patents could generate revenue. But how much? Time (hard to include in the calculations) will tell.

Also consider Maria Solares, former chair of the Huck Graduate Student Advisory Committee, who came to Penn State to work with Deb. Maria’s early life was changed by an inspiring teacher who not long after died from cancer. Ever since, Maria has been passionate about preventing more people dying like her teacher did. That passion is being realized because of her access to our instrument. How to include that empowerment in the calculations?

The board also heard from Tatum Cutler, a sophomore working in our facilities. She told them that the expertise she was gaining in our microscopy core was setting her up for an exciting career. But her greatest pleasure was derived from teaching microscopy to the very people who were teaching her in her first year at Penn State. How to include any of that in the calculations?

And then a Trustee just said it. Pointing at the instrument, Deb, Maria, and Tatum, she said: “The real ROI? This work might save women’s lives.”

We do important work. I wish you a refreshing holiday break and an impactful 2023.

- Andrew

As Huck Director, I have the privilege of saying the first words of welcome to our incoming cohort of graduate students (this year, 61). If there is ever a time for soaring Churchillian rhetoric, this is it. Our students are embarking on a major journey, one that will change their lives forever. And, if they work it well, their journey will make the world better too.

So, I stepped up to the plate and….

Talking to students after, I learned I might be more effective pursuing Twitter-ian rhetoric. In passing, I remarked that if the incoming students don’t feel very (VERY) stupid over the next few months, they are in the wrong program. Of all the wisdom I endeavored to impart, that brief message (all of 81 characters of it) hit home. Apparently, giving students permission to feel stupid brings them great relief.

I worry they should feel the need for that relief. Maybe it is my rose-tinted glasses, but when I started my journey, I too felt very, very stupid. But I left my home country and travelled halfway across the world to feel like that. It was invigorating. If you want to raise your game, how else would you want to feel?

I still seek that stupid feeling. And as colleagues who work with me can attest, I am pretty good at it. The astounding levels of my ignorance are revealed every day. But these days, it is (mostly) highly trained ignorance. That’s one of the very best things about a life scientific. You get good at stupid. You get comfortable with it. You seek it out. Because very interesting things happen when things don’t make sense, often extraordinary things. Recognizing and marinating in what you do not know is essential to being an effective scientist, because sometimes no one in the world knows either. Interrogating your ignorance is also hugely enriching as a person.

The value of interrogated ignorance is a key lesson we need to get across to students embarking on their graduate studies. If we can help them cultivate what Stuart Firestein calls ‘mindful ignorance’ (really another name for well-directed curiosity, and importantly different from willful ignorance) then we will change our students’ lives and the world for the better. Ignorance really can be bliss – however you do your rhetoric.

I hope you all have a good stupid year.

- Andrew

2021

It’s been a full six months since my last “Angle.” That’s not because I haven’t had anything new to share. Just the opposite, in fact. There’s been so much happening at the Huck, there’s really been no time to step back and comment on it all. Let’s see if I can get us at least partially caught up. This “Angle” is going to run a little longer than usual, but there’s a real whopper at the end you won’t want to miss!

First and most importantly – an update on our people, without whom there would be no Huck.

Since my last post in March 2021, several veteran staffers have departed our hallowed halls. Our long-time director of administration, Kim Ripka finally decided it was time to retire, having served Penn State since 1983(!). At time of writing, the search for a suitable replacement to serve as Huck’s managing director continues. That is one big reason there has not been “Angle” since Kim left. In addition, Huck’s IT director Scott Lingle, Metabolomics Core Facility director Phil Smith and accountant Antonio Brown have each made career moves as well. We wish each of them the very best in all their future pursuits.

On the other side of the equation, we’ve added several new folk to our ranks, and are interviewing others. With so much to cover in this Pulse, I’ll introduce them next time. But right now, I do want to give a big shout out to the folk who have taken the strain while we’ve been understaffed, particularly AJ Settlemyer, Brittany Grimes, Josh Yoas, Kelly Foster and Mike Uchneat.

These months have also seen a great number of new honors bestowed upon Huck faculty and students. What follows is just quick list of some I know about – there are certainly even more. Don’t be afraid to tell us yours. Our horn is always primed to toot for excellence.

Back in May, Stephen Benkovic was elected Foreign Member of the Royal Society and Nina Jablonski was elected to the National Academy of Sciences; in August Troy Ott was elected president of the Society for the Study of Reproduction; and the Entomological Society of America has just recognized our own Kelli Hoover and Flor Acevedo with new honors.

Proving that we Huck life sciences people are more than holding our own in the business world, Joyce Jose and Sally Mackenzie have just been awarded Eberly’s 2022 Lab Bench to Commercialization grants and David Hughes has been named on of Fast Company Magazine’s “Most Creative People in Business 2021.”

Within our own organizational structure, Jennifer Macalady has taken over the directorship of our Ecology Institute from Erica Smithwick and Dan Hayes is now at the helm at our Center for Excellence in Industrial Biotechnology, having taking the torch from Andrew Zydney. And please help me congratulate our latest crop of Huck Chairs – each of whom has made outstanding contributions to the life sciences from their respective fields: David Hughes, Claude DePamphilis, and soon to be announced: Robert Sainburg, Douglas Cavener, and Vasant Honavar.

Finally, I would like to call your attention to just a few of our stellar graduate students, who never cease to amaze and inspire. In April, Physiology student Isabel da Silva earned top honors in the Health & Life Sciences category of the 2021 Graduate School Exhibition. In July, a paper authored by Bioinformatics and Genomics student GM Jonaid, who works in Deb Kelly’s lab, scored the cover of Advanced Materials. And finally, just this week we learned that another BG student, Chen Wang, has been selected by The American Society of Human Genetics as a semifinalist for the 2021 Charles J. Epstein Trainee Awards for Excellence in Human Genetics Research.

Then there’s the technology. In April, we cut the virtual ribbon on our new Sartorius Cell Culture Facility, thanks to the generosity of our outstanding global partner of the same name. And we made a serious upgrade to our X-ray crystallography facility with our newly acquired BioSAXS-200nano 2D-Kratky system.

In terms of research output since March, where do I even begin? Just browse through the headlines of the 82 news stories published to the Huck website since April 1 to get an inkling of the incredible variety of world-class, interdisciplinary science that continues day in and day out around here. (You’ll see even more awards listed there too). All this activity, even in the midst of a punishingly stubborn pandemic. It’s truly staggering.

Speaking of the pandemic, which we all had hoped we’d be starting to view in our rearview mirrors by now, it would appear that there’s no end in sight to the continuous stream of controversies madly churning around it. I myself got to experience this in an intensely personal fashion in August, when the world’s most popular podcaster, Joe Rogan, briefly discussed a paper of mine from 2015 in relation to virus evolution.

Rogan’s 3-minute mention has been viewed now by over 3m people and resulted in the paper being catapulted from relative obscurity into the top 125 all-time most mentioned articles on social media – out of 18.9 million followed by Altmetric. My inbox has yet to recover, and the paper’s ranking continues to rise. For those who want to see my official response to this situation, here’s the piece I wrote for The Conversation.

Putting all that aside, the thing that I am honestly most excited about is the opportunity to support more risky and innovative research here at Penn State. I don’t ever want to look back on my career and learn that I missed out on supporting the next Katalin Karikó – or Steve Benkovic.

With this fact held firmly in my mind, I want to encourage every researcher reading this who has a wild idea for a life sciences project to take a very close look at two current opportunities that Huck is sponsoring right now.

The Huck Institutes Innovative and Transformational Seed (HITS) Fund has been running right through the pandemic and continues to support ideas that are too innovative to win NIH, NSF or USDA funding. And it gives me inexpressible amounts of pleasure to announce – if you haven’t heard yet – that we have just launched an additional grant program with the same kind of bold zeitgeist.

Thanks to the deeply appreciated generosity of the Benkovic Family Foundation, Huck is now co-administering – along with Eberly’s Chemistry Department – the inaugural call for proposals for the Stephen and Patricia Benkovic Research Initiative. We are looking to fund some really creative work with this new program, to the tune of $1 million this year.

Proposals for both programs are due November 1, but we want to hear about your ideas well in advance of that. Please do have a look at those links and get in touch. This is what it’s all about.

- Andrew

Thirteen months ago, almost to the day, I first asked Huck’s infectious disease community about our research response to humankind’s newest virus. Since then, it’s been a roller coaster for us all. But Friday last, I had my first discussions with university leadership about our post-pandemic infectious disease research needs. Hard not to get a charge of enthusiasm, despite pandemic fatigue. It’s not yet peacetime as we knew it, but the firefighting is done. We’re starting to re-imagine our needs and opportunities out to the middle of this decade and beyond.

There are stirrings of this right across campus. People are starting to climb out of the trenches and look to the future. I’ve been massively uplifted by the faculty response to the University Health Science Council call for proposals for a new initiative to tackle significant health challenges. Things like obesity or antimicrobial resistance or cognitive aging or chronic stress. We’re looking to establish consortia of faculty with complimentary expertise in multiple research domains at multiple scales, perhaps from atomic resolution to law, policy or populations. This requires our leading minds to join up excellence across campus and then think very significantly about what new expertise would cause a step change in impact.

The deadline for initial proposals is next week, but the informal discussions I’ve had with many groups has really got me fired up about where this is going. We should be able to unleash exciting and potentially really impactful endeavors. Watch this space.

Of course, we still have major challenges. But compared to what I thought in July….Back then, I was incredibly concerned about the decision to bring the students back. I did not know anyone in the infectious disease community that thought it a good idea, and the mathematical models did not look good. But then the Fall brought two major, totally unexpected breaks: (1) COVID-19 turned out to be far less severe in students than the early data suggested, and (2) viral spillover from students to the non-student community turned out to be nearly non-existent.

Never have I been so pleased to be proven totally wrong. If we all keep our eye on the ball and get vaccinated as soon as we can, things should look very much better by late summer. Time to recover our mojo and begin the re-imagining.

- Andrew

2020

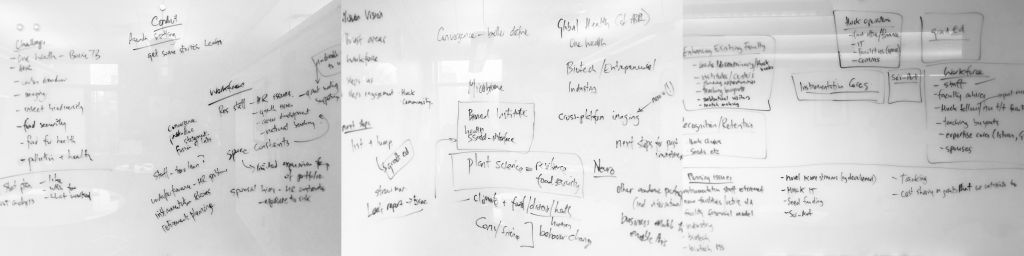

This time a year ago, a COVID patient had been hospitalized for the first time. No one had yet died. Blissfully unaware of what was to come, I was taking end-of-year pictures of the whiteboards in my office. They were covered in Huck’s ambitious plans for 2020.

None of those plans came to fruition.

Instead, the year rapidly evolved into a mad rush to respond, adapt and survive. It turns out that piloting a ship in a storm is a real challenge, especially when your navigation system’s being radically overhauled (SIMBA…).

But the Huck crew was and remains magnificent, and I’ll be forever grateful for the calm heads and hard work that got us through the year. For a playful recap of what we managed to collectively pull off, I invite you to enjoy a laugh or two at our consensual expense by watching our tongue-in-cheek exploration, "2020: What (in the Huck) Happened?" (Laughter is, after all, the best medicine).

Reflecting personally, I am struck the photos I took in 2020. Absent travel and restaurants and social gatherings, my photos are of the everyday things around me. Apparently, I was looking harder at the ordinary, and seeing more there.

When we can, I’m eager to circle back to those ambitious plans left on my white board back in 2019. I miss them. But after all the harrowing and discordant trials and tribulations of 2020, it strikes me that the ambition to improve upon the status quo, while seriously important, isn’t always the most important thing.

There is also beauty to be found in the ordinary.

Warm wishes to all for a joyous and restorative break. See you in 2021.

– Andrew

When I moved to the US in 2007, one of my favorite discoveries was Thanksgiving. There is no equivalent in New Zealand or Europe. I really like it because it’s not been overly commercialized, even the excessive food and drink. Instead, it’s about people. And best of all, it’s a nationally scheduled opportunity to reflect on what’s good. This year, of all years, crowding out the bad and focusing on the good has never seemed more important. I hope everyone in the Huck community takes the opportunity.

For me, I feel exceptionally thankful for the many good things in my personal life. I am also very thankful for the most breathtaking colors of the thirteen Fall seasons I’ve experienced in Happy Valley. The months since lockdown have also made me even more grateful for the staggering power of the knowledge-generation system we call science.

Look at how fast humanity can learn things. I’m getting huge satisfaction watching the scientists on campus getting funding and even better very cool COVID science done, much of it made possible by our seed funding. I’m also very grateful for the people I’ve gotten to know and see in action while collaborating on the various teams that have formed up to mitigate COVID problems in Happy Valley and beyond. I’ve always enjoyed working with scientists from disparate disciplines, but in these efforts, I’ve worked with lots of non-science academics as well as many operations people, which has been stimulating and eye-opening. For all that I am very grateful.

From talking with staff, students and faculty, I know I am one of the lucky ones and many people are having a really tough time. It’s been an exhausting and uncertain year, with more to come. But I take heart in this holiday. Consider that our observance of Thanksgiving on the last Thursday of November was officially decreed by Lincoln in the middle of the Civil War. In the midst of all that chaos, he and those around him felt the need for the nation to give thanks.

I hope you all get the breathing space to reflect on what’s good. Happy Thanksgiving.

- Andrew

I don’t know about you, but I feel like research has got a whole lot harder. At the best of times, it’s never easy, and these are surely not the best of times. On top of all the COVID-related issues—masking, mandated lab de-population and cleaning shutdowns—we have the national uncertainties and affronts and our institutional own-goals. Budgeting, purchasing, hiring, regulatory: everything is harder. I can’t imagine how much stress is added if you have to juggle small children or on-line schooling while yourself teaching remotely. I feel like I am swimming against the tide, with huge activation energy required to eke out modest wins. I see frustration everywhere, and I share it.

It’s no wonder research activity on campus has really slowed. Our research buildings are depressingly empty; supplies and reagents coming into Huck buildings are 20 percent of what they were. In my own group, we’ve dropped our meetings with collaborators to two-weekly because none of the labs are producing enough data to fill the weekly schedule we had in peacetime. And if we ever doubted it, we’ve learned just how much science is a social enterprise. I so miss the seminars, workshops, brown-bag lunches, the vibrant corridor conversations, whiteboarding with my people. Zoom and email are buzz crushers.

Given all that, well, I don’t know about you, but I know my blood pressure will be better if I idle my research until winter has gone. But lately, I’ve increasingly felt the need to ramp things up. Research generates a sense of purpose and progress even when it’s hard. And these times will end (yes, even SIMBA will one day be fit for purpose). Emerging from this with strong data in hand, ideas for the new, and my people firing on all cylinders has never seemed more important. Plus, we now know that with care, a lot can be done in the lab.

My group has worked out the maximum capacities the lab can handle at the moment and is working shifts to get it done. Further shutdowns may come, but that seems increasingly unlikely given the research buildings are probably the safest place outside of home, so we’ve started experiments that will take weeks. Proud of one of my post-docs who has kept a large and important experiment going through all of this, and another who taught herself bacterial genome bioinformatics and has just added very significant value to a paper that had been wholly phenotypic.

As for the Huck Exec, sick of our weekly Zooms, we’ve resolved to meet in person next week, socially distanced in one of the empty conference rooms. Looking forward to trying it with my group as well. If folk can teach in-person, surely we can hold lab meetings in person?

I’d be very interested in hearing how others are coping. What are you able to do? What do you see others doing that facilitates progress? How have you pivoted or found new niches or opportunity? I see a few labs going full bore. Share your story with me and we’ll share with the Huck community. Resilience is a community property, even in socially distanced times.

- Andrew

Just a brief comment this month. It’s really a plea for these trying times.

For the foreseeable, no magic solution will melt COVID away, least of all in Centre County. So, our university and community leaders at every level are being forced to make choices where none of the options are what we would like. That’s true for each and every one of us too: we are all engaged in a search for least-bad options. That sucks. But the one positive thing we can choose is our reaction to that reality.

My observation is that anger or blame seldom builds resilience in individuals or in a community. How about we try something constructive and positive instead? Let’s take as a default assumption that everyone has good intentions, because they almost always do. Let’s take as a default assumption that everyone is trying their hardest, because almost everyone is.

None of us like this new and far from perfect world find ourselves in. But we’re all smart. Let’s, as they say, try to distinguish ourselves – and our community – by being kind.

- Andrew

The vastness of the cosmos is humbling. But Google the molecular structure of the tiny and rather beautiful SARS-2 spike protein. Even if you’ve never had COVID-19, that protein is affecting your health and wellbeing and will for some time. A protein that has humbled humanity.

As I write, students are returning to University Park from all over PA, the nation and the world. So far, COVID has only lightly touched Centre County, but that’s about to change. (I’m not alone in thinking that, but for the record, my pessimism is not universal -- I was yesterday labelled part of the doom and gloom brigade). Whatever happens, the coming weeks and months will surely be more of a challenge than the last exhausting six months. Buckle up (and mask up).

What most sucks about COVID is the complete absence of good options. Right now, it’s all about trying to make the best of a bad job. It’s zero fun and, at times, terrifying (lives are literally on the line). But let me share a positive.

It turns out that there is nothing like a crisis to breed real interdisciplinary teamwork. I thought I knew what interdisciplinary meant. COVID@PSU has opened my eyes. I could share many examples but consider what is now the Centre County COVID-19 Data 4 Action Project (D4A). This is a joint collaboration between Huck, SSRI, and the CTSI. It’s aimed at determining the social and economic impact of COVID-19 locally, and to monitor changes in virus attack rates and immunity going forward in time.

It will empower local leaders to make data-informed decisions about how best to protect community health and wellbeing. We also hope it will generate novel discoveries—though there are much easier ways to do that. All the faculty involved would prefer to be doing their pre-COVID research, but as community members who care deeply and want to protect their own families, friends, colleagues, and neighbors, they’ve come together around this project. As Matt Ferrari, one of the project leads puts it, “We’re a world-class research institution, so we should be the best-informed community going forward”.

When the costs got too much for Huck and SSRI, Provost Nick Jones stepped up with funding that will get us to Christmas. Hundreds of residents have now given blood and answered surveys and agreed to further participation in the months and years to come. (We’re still recruiting if you want to take part).

An army of nurses, regulatory folk, purchasing folk (think freezers, tubes, bar codes, and PPE), parking officers, lab volunteers, IT people, consenters, and communicators have been involved, as well as folk at Mount Nittany Health who are partnering with us on the initial testing, and local community leaders who have supported and helped get this off the ground and the word out—it’s all been fantastic.

We’ll have our challenges to keep going, but I have faith that once people see the utility of the data we are generating, we’ll be able to find the resources to go forward for many years. It’s an exciting prospect: world-class science to help our own community, with possibilities to scale across the State and beyond.

All of which has really reinforced my belief that one way to achieve Huck’s mission to make more impactful research happen is to bring people with disparate skillsets around defined problems that are worth solving. In contrast to discipline-orientated teams, problem-orientated teams are necessarily more diverse, more likely to have impact, and less likely to self-generate without the convening power of research institutes like Huck.

The hard part is not finding problems worth solving. The world is full of them. The trick is to find a problem urgent enough that people pivot, climb out of their comfort zones, and work together. A humble little protein can make us do that. What else?

- Andrew

Huck’s Pulse newsletter is a little different this month folks, for obvious reasons. In lieu of my regular “Angle” column, I offer the following three items: (1) COVID comms, (2) COVID research, and – wait for it – (3) non-COVID research.

(1) Like a giant celestial object, a tiny virus has warped time. For some in our community, everything has slowed to a crawl. Others are racing faster than ever. Our infectious disease researchers, for example, have been accelerated to warp speed. Not only are they heavily involved in COVID-research, they are being inundated by requests for expert opinion from journalists, university leadership, the curious public, family, and colleagues. This is one aspect of a pandemic preparedness I had never foreseen: a hunger to have the media deluge interpreted.

In an attempt to push out our expertise without crushing the experts, the Huck com team has collaborated with Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics (CIDD) faculty to launch an “Ask CIDD” initiative. The public submit their COVID questions and our team answers the most popular ones via video with the most scientifically accurate, up-to-date info available. So far, they’ve been able to publish one video per day, M-F. Subscribe to these videos here.

(2) Since our last newsletter (really, just a month ago?), we stood up what we’re told was the first coronavirus seed grant scheme at any US university. So far, we’ve got $1.25m to researchers, with more to come. It’s been amazing. Within a day of going live, all the OSVPR Research Institutes were involved – which speaks to the fantastic working relationship we have. Less than a month later and we’ve had well over 100 proposals! You can see some of what we’ve funded in the first rounds here .

The intellectual breadth of what PSU has to offer is stunning: everything from angstrom-resolution of the viral surface to vaccines and therapeutics to diagnostics to hygiene to patients to hospital management to environmental sampling to global health modelling to social and community population health….. Whatever happens in the coming weeks and months, it has made me very proud that we – the Penn State Research Institutes – are capable of supporting work with outstanding promise with such speed.

Thanks so much to all the Huck staff who, behind the scenes, have also been at warp speed, the Huck Exec, my fellow Institute directors and particularly Beth McGraw who is chairing the process (now time for a G&T?). Most of all, thanks to the researchers who have stepped up with ideas, expertise and technology. Godspeed. Make us proud.

(3) In gentler times (really, just three months ago?), I wrote of why we at Huck are passionate about supporting truly high-risk/high pay-off research (if we don’t, who else will?). Despite everything that is happening around us now – perhaps even more so – we remain totally committed to that view. Penn State, the nation and the world are better when our scientists think out of the box. So, we are going to continue with our HITS seed fund. We’ve pushed the deadline to May 1 give you and us some breathing room, but otherwise we’re still going for it. Our screening process will be simple: (1) if the idea works, will it have big impact?, and (2) will our support de-risk it for conventional funders? Think bold, folks.

At this moment, all of us face a chaotic and uncertain collective future – one in which countless people have had their lives completely upended. Those of us who are still able to do meaningful work in the face of it are among the most fortunate in the world. Let’s make the most of this opportunity to be of service and make a positive difference.

If not us, who?

- Andrew

Unless something miraculous happens, humanity just gained itself another virus. With luck (and a lot of hard work), a highly effective vaccine will become available, and herd immunity will render the latest coronavirus a thing of the past. But we’ll have to be awfully lucky: humanity has only ever eradicated one human pathogen (smallpox), and vaccine development takes years. Right now, we can only guess at the deaths and societal disruption to come in the next few months.

Throughout human history, infections have spilled from animals into humans, as did this one. When humans lived in small groups, many outbreaks undoubtedly fizzled out. But as human populations grew large enough, spillover pathogens were able to permanently sustain themselves on us (measles). These days, advances in microbiology and public health make it possible to catch some early and eradicate them (SARS). But many get away (HIV, 2019-nCoV).

Odds are that spillovers will become more common. The human population has doubled in my lifetime, and it will continue to rise for decades. That’s an awful lot more animal-people contact, especially as resources get stressed and environments disrupted. Combined with density-dependent transmission and unprecedented human mobility across the planet... well, we’re in parameter space no species has ever experienced.

It’s hard to judge the threat. We don’t yet know what the COVID-19 fatality rate is, but it looks substantially lower than SARS. We don’t know if the next spillover will be worse or better; right now, we don’t even know enough to predict whether 2019-nCoV itself will evolve to become more or less virulent in the coming years.

Like many challenges facing humanity, science is key to spillover mitigation. Here at Penn State we have one of the largest groupings of co-located infectious disease scientists anywhere, with some of the best facilities. Moreover, our expertise lies across all the scales involved, from angstrom-level structure and chemistry on the surface of virus particles (Center for Structural Biology) to global pandemic preparedness and vaccine implantation strategies (Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics). Hear three of our sharpest minds talk about their work on infectious disease dynamics in this month’s Symbiotic Podcast.

As we confront the challenge of global outbreaks, effective international collaboration is an absolute necessity. With that in mind, I am proud to say that Penn State was the first university in the US to sign on to a global coalition pledging rapid and open access to research data concerning the outbreak.

Whatever happens, we want to stay at the forefront. The life sciences are going to be key for dealing with spillovers, but so too the social sciences, law, policy, economics, communication science, advanced computing and mathematics, and new sensing technologies. Penn State’s leadership is committed to pushing boundaries across each of these fields.

For our part, Huck will continue to not only build on those strengths but also to facilitate seamless intellectual movement between them.

We have to. There is going to be a lot more to do.

- Andrew

If you imagine the 21st century as a five-day work week, hitting 2020 means Monday is over. What should we do with Tuesday?

At Huck, we’re aiming for more disruption and failure. But not for their own sake. We’re after disruption and failure with a purpose. Our thinking is simple. Truly innovative and transformational research never starts with a ‘safe bet.’ That means we have to be prepared to make unsafe bets...

So, with great enthusiasm and a BIG financial gulp, we are resurrecting the Huck Innovative & Transformational Seed (HITS) Fund.

This program is designed to foster projects with knock-your-socks-off potential that are too risky to secure conventional support. The application is simple. Persuade us that your idea will change important games if it pans out, and that none of the usual suspects will fund it. If we buy your argument, we’ll give you all the money we think you need to de-risk things for traditional funders. We’ll eat the financial loss if you fail, no questions asked. In return, you have to be ready to eat the time, bandwidth and opportunity cost if your idea is wrong.

Brave enough?

Huck ran this scheme before, just once, in 2012. The rubric was conceived on the I-99, when then-Huck Director Pete Hudson and I were coming back from DC, lamenting the incrementalism we’d just experienced.

Around that time, I vividly recall newly recruited Assistant Professor Marcel Salathe assert that ‘When safety comes first, America is lost’ (a line he attributed to a Roosevelt, but Google does not). That sentiment so captured the America of Possibilities I imagined as a child in New Zealand. I was eager to test it out and so was Pete.

There were 40 applications. I was amazed and disappointed we had so few. Huck does business with more than 500 faculty and even more grad students and post-docs, and only 40 have high-risk/high-payoff ideas? Worse, half the proposals were shovel-ready for NIH or NSF. Great stuff, but not bold. Of the remaining 20, we took a gamble on five or six. You can see four successes here. Clearly we did something wrong: 4 out of 5-6 is freakily successful.

Going forward and with a view to permanently raising aspirations, we will run the HITS call twice a year for as long as we can keep the money going. We want everyone at Penn State to incubate bold, high-risk/payoff ideas. Develop them. Bring them to us.

Choosing the proposals to fund will of course be a challenge. I am delighted to announce that Steve Benkovic—someone who knows a thing or two about high-payoff, risky science—has agreed to co-chair the process with me. We’ll populate the selection panel with an outsider or two and then, depending on applicant subject areas, we’ll ask big-thinking Penn State professors with subject expertise and no conflicts of interest to get involved.

Likely the selection panel will vary over time. We’ll get shortlisted applicants in for discussion and figure out with them how to hold their feet to the fire while simultaneously nurturing their idea to an agreed “GO/NO GO” point.

Everyone at Penn State should have at least one high risk-high payoff idea they can’t get funded. This is your chance to give it your best shot. Take a risk. Life is short. Bring us the ideas that would change the world if they pan out.

If nothing else, it will make for an exciting Tuesday.

- Andrew

2019

Nearing the end of my first year as Huck Director, I find myself pondering failure.

In a previous life, I did a lot of climbing in the New Zealand mountains. Among the climbing fraternity, well-intentioned failure was seen as the flip side of ‘no guts, no glory’. Failing was okay (so long as you stayed away from stupid). Indeed, the epic retreats, the disasters and the rescues, those became the folklore; the successes were just lines on a vitae. The folk really pushing the boundaries – the new routes, the winter routes – failed more often than they succeeded, but they changed what the rest of us did, aspired to, and even thought possible.

Science is also about pushing boundaries. Over the last year at Huck, I’ve heard a lot of stories about success, yet I can’t think of anyone telling me of abject failures. You know, the kind of thing that if it had come off, the Nobel would be in the bag, but instead it was a blow out. With very few exceptions, I hear no tales of breathtaking high-risk/high-payoff projects. I hope those projects are out there, because humanity needs game-changing science more than ever.

Bureaucratic risk aversion works against high-risk/high pay-off. In the name of efficiency and oversight, institutions carefully guard every dollar, worry about every hypothetical lawsuit, try to make every minute count. This rapidly leads to incrementalism, no more so than at the NIH and NSF. At both agencies, standard funding decisions have become so risk averse that separate schemes for high risk work have been created.

Penn State starts the new decade with a strategic planning round. I want to think more about how we can create an environment where our researchers can take major risks and be open about it. Money is some of the answer, but I think more it is about the culture. We need to celebrate those trying high-risk/high payoff. Minimally, that means enjoying each other’s tales of failure. Perhaps we need to include failure stories in future Huck newsletters.

Nobody wants everyone to gamble everything on crazy stuff. And we should all be on the lookout for the low-risk/high payoff projects. But they are rare. More common are low-risk/low payoff projects. We often need those in our portfolios to keep the lights on, but they will never change the game.

Just imagine a situation where everyone, from new grad students to professors to university administrators, could point to at least one high-risk initiative they took on. How many more high-payoff outcomes might emerge, and how much gloriously rich folklore would result from the failures?

There are endless routes to the top of the mountain, but new ones cannot be recognized until someone has the courage to envision them, gear up and have a go, even when success is far from guaranteed. What can Huck do that will be a game changer if it works, and nothing more than a learning experience if it does not?

My very best wishes for the Festive season. May your 2020 involve unsettling (intellectual) risk.

- Andrew

Last month, Penn State hosted SciWri 2019, a conference of 500+ science writers from all over the country. Huck was one of the biggest sponsors of the event and that meant we got to host four core facility tours, an insectary field trip, a live podcast panel, and a wildly popular Science Trivia game for the visiting community of journalists and academics.

Big shout out to Huck’s communication team, led by the irrepressible Cole Hons, for their enormous efforts. I am confident that some of the leading science journalists and writers in the country now have a much better idea of the breadth and expertise residing under the Huck umbrella.

My own immediate personal outcome of our involvement was an interview with NPR, conducted on the heels of a major new report about antibiotic resistant germs from The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This was the result of a talk I was asked to present by the organizers of SciWri 2019. Even challenging title they gave me – The Evolutionary Battlefield of Medicine: New Tactics Needed – seemed not so far from what I often talk about.

But as I dusted off one of my standard academic talks it was clear that something very different was called for. Nothing focuses the mind quite like the prospect of talking to an audience of smart, curious people who know nothing about your specialty – when you also know there will be subject matter experts in the room.

I was forced to think about the very big picture of what my research group and collaborators are about, and that was exceedingly stimulating. It also made me think through what differentiates our work from the mainstream and enunciate that. To me, it’s plain as day. But it turns out when you try to explain it to an audience like that, it’s not actually so obvious. Preparing the talk also made me rethink some of our research priorities. From 50,000 feet, you can really see the forest. I began to wonder about things we had not followed up and had new ideas about new research directions we might try.

I came away from the experience convinced that more faculty should do this kind of presenting. Of course, we can’t have a Science Writers convention every week. But we do have the Millennium Café, 10 a.m. each Tuesday on the third floor of the Millennium Science Complex. There, the Material Research Institute’s ever energetic and facilitating Josh Stapleton not only gets two speakers to talk about their subject expertise, but goes to extraordinary lengths to make sure they aim their expertise at non-specialists and possible collaborators outside their disciplines.

Not all faculty pull that off (sometimes, it is amazing what some geeks think constitutes an accessible talk). But many faculty do. Invariably, I find those sessions to be more reliably interesting than expert seminars in my own specialty. (They’re also shorter talks so you are not stuck for an hour if someone is droning on). The coffee and doughnuts are good too. I go whenever my schedule allows.

In today’s frantic drive for academic metrics – grant dollars in and scientific papers out – it is all too easy to lose track of the point of it all. As a hedge against this tendency, we should all be forced to take the time to step back and take a look at our position in the world, and then explain that to others. I think the discipline of talking to curious, smart non-subject matter experts is one outstanding way to avoid incrementalism – and, at least for me, to ask whether our day-to-day work in the weeds is truly aligned with an essential goal; understanding the forest.

- Andrew

Communication is critical to Huck’s mission of collaborative, impactful discovery. Because, let’s face it: scientific discovery is nothing but self-gratification if stakeholders don’t know about it. That’s why we and our partners put a lot of effort into communicating science. But it’s obvious that we could all do better: there is immense scope for new ideas and experiments. So bring us your ideas. We’re up for taking risks.

I see two aspects of communication related to what we do at the Huck that are ripe for new advances.

First, human behavior rarely changes of its own accord in response to scientific discoveries*. This is problematic, because overcoming most challenges facing humanity requires people to behave differently. The global challenge I am personally researching is the evolution and emergence of so-called superbugs, bacteria that can no longer be killed by previously effective antibiotics. By some estimates, these bugs will kill more people than cancer by 2050. A big part of the solution involves using antibiotics only when we need to, but that is easier said than done. For example, physicians know that prescribing antibiotics against viral infections is worse than useless, and the government keeps reminding them, but the problem persists at scale. Why? And if advice that simple is hard to follow, how will more complex solutions life scientists produce ever have impact?

I think communication science has a lot to offer. As a social science, it has the potential to uncover strategies that will lead to behavior change when scientifically-sound advice is not enough. In this month’s Symbiotic podcast, you can hear about my forays into this realm with Erina Macgeorge of the Department of Communication Arts and Science (CAS) in Penn State’s College of Liberal Arts.

We at the Huck are so encouraged with what is possible that we want to further build our partnership with CAS. We already have two faculty co-hires and are closing in on a third with a fourth slated for 2020-21. Additionally, we are preparing to launch an NIH-funded graduate course melding life and communication science (leads: Steve Schaeffer, Biology, and Rachel Smith, CAS). Finally, we are partnering with CAS on the Communication, Science and Society Initiative (CSSI). This is an experiment aimed at bringing communication and life scientists to work together on some of the major challenges facing humanity. It is being led by CAS’s Jim Dillard. Do reach out to Jim or our lead, Huck associate director Connie Rogers, if you want to know more. In a future column, I’ll describe the exciting partnership we have with the Social Science Research Institute to expand the work still further.

The other aspect of communication ripe for advances is central to Huck’s raison d’etre. We expect major advances when traditional disciplinary boundaries are spanned – but the most obvious sign that this is actually happening is when the participants cannot understand each other. Yet when jargon, concepts, theories, methodologies and scientific cultures are foreign, intellectual dissonance can lead faculty to go back to their disciplinary comfort zones. As I learned with Erina, it takes time to build trust and to understand each other’s language and way of thinking. I really believe communication science can also help address this problem.

Increasingly, people are talking of a science of science. A major part of that enterprise should be the study of scientist-to-scientist communication. Penn State is as good at peer-to-peer communication as any university and far better than most – but we have to get even better. Solutions to the world’s most serious challenges—from food security to neural basis of consciousness—require that truly transdisciplinary teams are unleashed. That requires superb peer-to-peer communication. The institutions that can do that best will change the world.

- Andrew

*One of the few examples might be the lines of parents queuing for the polio vaccine in the 1950s, when polio epidemics maimed American kids.

A curious thing about the Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences is that no other university appears to have anything quite like it. Think about that. Demonstrably, we aren’t necessary.

I love that. It means we exist only to make a difference. Good things, often excellent things, will happen if we do nothing; clearly, Colleges and Departments can flourish on their own. That perspective underpins everything I am trying to do as director. “If we do X, what difference will it make?” Of course, that’s also the way our game-changing staff and faculty think: “What difference am I making?”

‘Difference’, I think, boils down to impact, a hugely slippery concept. Many university administrators measure impact in terms of grant income, or financial efficiency, but of course that’s nonsense: dollars are the input. Impact is an output. My colleague Matt Thomas goes further: we should care less about outputs and more about outcomes. Scientific papers are outputs, and they really can generate outcomes. But papers needn’t be our only outputs, and infuriatingly, outcomes, even from papers, are really hard to measure. Sometimes, outcomes can be captured by citation counts or altimetric scores. But not always. If you actually solve a real world problem, it is often soon forgotten. Failing to solve a problem in an interesting way can better generate social media metrics and citations.

I think a real measure of impact is the extent to which we change the beliefs and practices of a constituency. Huck’s target constituency is staggeringly diverse. Certainly it includes our global fellow academics - a very important and exciting audience. But our constituency could also be policy makers (EPA, WHO), or the commercial landscape (Google), or those charged with human well-being (e.g. physicians, farmers), or the lay public, striving to better understand themselves and their world.

In the years to come, I very much look forward to the struggle of trying to balance that portfolio, perhaps one of the toughest challenges in scientific leadership. Right now, Huck is working on all the impact-enhancing initiatives we can construct. Bring us more. We exist to make special things happen.

- Andrew