On The Rise: Molly Hall Brings Data Analysis to Child Development

Most of the life science labs at Penn State look a lot like, well, labs. There are beakers and pipettes and samples, with grad students and postdocs scurrying past cutting-edge instruments and their attendant warning signs in lab coats and gloves. That’s not the case with Molly Hall’s lab.

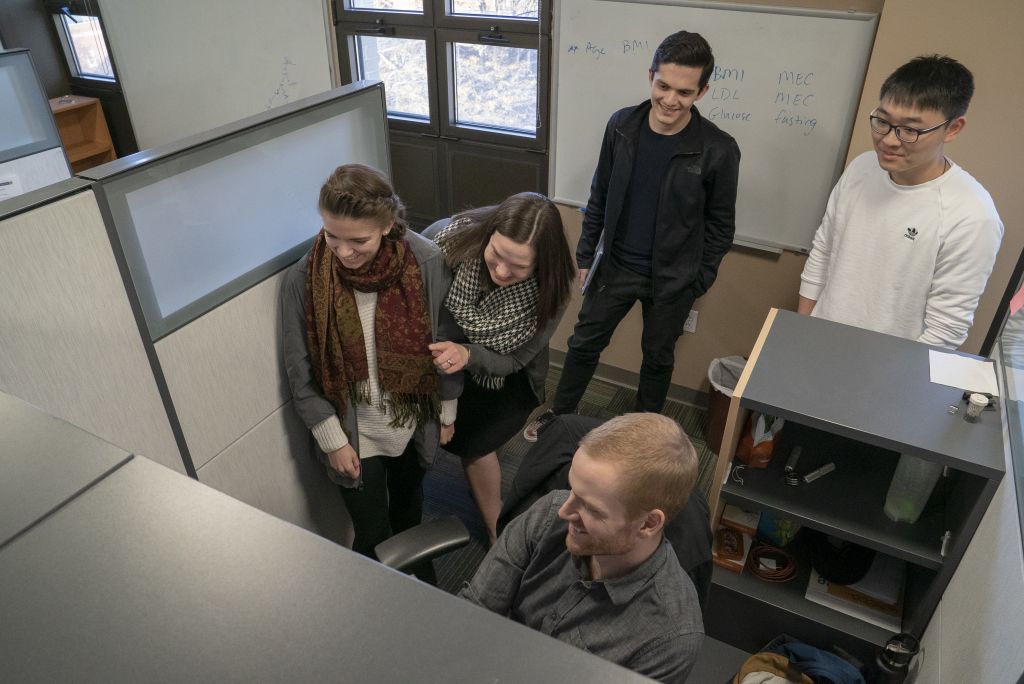

Nested in an alcove of cubicles in a far corner of the top floor of Wartik, Hall’s cadre could pass for an app startup team, or maybe the staff of a small-town newspaper. The whiteboard that dominates one wall is covered in doodles, not diagrams. But don’t be fooled by first impressions: the members of the Hall Lab are serious bioinformaticians, and they’re knee-deep in exciting, big-picture life sciences inquiries.

“The goal of our research is to build computational software that makes predictions about disease outcomes,” said Hall, an assistant professor of veterinary and biomedical sciences. “We’re looking at genetic data, we’re looking at environmental data, and we’re looking at a lot of other, multi-omic data. And epigenetics as well. We’re really interested in modeling the complexity that exists in biology to be able to make those predictions about disease outcomes.”

Multi-omic data has major implications for predictions on individuals’ health.

If you have a large population of people with similar situations all reporting the same medical issues, you’ve got a trend. For bioinformaticians and developers, every person’s medical status is a goldmine of potential data points, and like any set, it gets more accurate with more data.

Morris Aguilar, an MD/PhD student in Hall’s lab from the Bioinformatics and Genomics program, wants to use this data for new technical innovations to “hopefully build applications that can augment a physician’s ability to detect and prevent disease.”

A project currently at the front of Hall’s mind is a collaboration with Dr. Jennie Knoll, a professor in the Human Development and Family Studies department, that is funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. It’s long been known that child maltreatment has serious impacts on future health, but less is known about how developing under such stresses could affect biological changes in children, and the implications stress or trauma-induced changes can have on their future health outcomes.

“It’s a huge study—unprecedented—which is looking at the effects of child abuse,” said Hall. “She’s recruiting 1,200 children; the goal is to have 900 children who’ve experienced maltreatment and 300 who have not. They are looking at a number of different measures to look at the process of biological embedding of the stress of child maltreatment, to better understand the mechanisms that lead to later adverse health outcomes that are associated with child maltreatment.”

Hall’s group is contributing to the many different biological data that they’re already collecting.

“We’re adding metabolomics in collaboration with Dr. Andrew Patterson, who is a professor in the veterinary and biomedical sciences department. He’s also the director of the metabolomics facility here at Penn State and he’s also in the Huck. His lab’s been teaching members of my lab how to collect and analyze the data. We’ve collected metabolomics data for the first 250 participants of the study and now we are pre-processing these data and working to do the first analysis.”

The Hall Lab is analyzing data obtained by applying liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques to urine samples obtained from participants. They’re looking for variations in metabolites, what Hall describes as “small molecules that are affected by changes in the genome or the environment.” She says that the metabolome can be thought of as a bridge between the genome and phenome.

“(LCMS and NMR) both show us what metabolites are in the urine, in different ways,” said research technician Nicole Palmeiro. “We’re given different sets of information and whenever we look at concentrations, or how high the peaks and the waves are, or where they align on the spectrum, that tells us what kind of chemicals we’re looking at. Later, we’ll be able to see their physical features, build a compound, and say ‘hey, this is the metabolite we’re looking at.’”

This work is made possible by a 2018 Penn State Human Health and the Environment seed grant, funded by the Huck and the Social Science Research Institute at Penn State.

“They were excited about this collaboration because it bridges the life and social sciences,” explained Hall. “One of my new initiatives for this project is to specifically link these metabolomic features to neurodevelopment outcomes. There is a known effect of child maltreatment on neurodevelopment, so we want to see if there might be any metabolic features at play as well.”

Hall, who last month was awarded the Dr. Frances Keesler Graham Early Career Professorship, was deeply motivated—as a researcher, as an educator, and as a parent—to cross disciplinary boundaries in service to a highly vulnerable segment of society.

“I don’t think it’s something that you can ever put aside,” said Hall of being a parent and teacher working on such a delicate topic. “I was really motivated to work on this project with Jenny and Andrew because of both my academic background in human development and understanding how important the process is of developing from childhood to pre-adolescence to adolescence.”

“Working with children in that time period is important to me. Being in schools as a teacher, I have worked with children who have, unfortunately, experienced trauma. I’ve seen the huge impacts that has on their life and their education and their general well-being. It’s important to me to understand the mechanisms that lead to health disparities in children who have experienced abuse so that we can best mitigate those adverse outcomes.”

Hall’s experience in childhood education also informs her approach to mentorship: it’s a big tent, and there’s room for anyone who wants to do good science. Her lab members are confronted with challenges for which they need to build entirely new sets of technical skills to complement their scientific educations.

“I was a middle school science teacher for four years,” she noted. “A lot of people think that science is not accessible to them: a lot of people who are not in the sciences, a lot of children think that it’s something that you’re just born with the ability to do and to understand, and I don’t believe that at all.

“Anyone can learn science if they’re passionate about it and they have good teachers. I was passionate about that as a teacher, and I bring that to my current classes that I teach, and to mentoring. It’s important for people at the graduate or undergraduate level to know that they can get through it. Everyone can do it. I do believe that.”

Hall’s personal touch and her belief in the ability of anyone with the requisite passion to do high-level science resonates not only with all the people working in her lab. MCIBS student Kristin Passero describes Hall as inclusive, attentive, and organized.

“When I first started here, Molly said that it would seem like everyone else knows what they’re talking about, but you shouldn’t be intimidated by that,” said Allison Ludman, an undergraduate researcher, because “none of them knew what they were talking about at the beginning. As an undergraduate, it would be easy for others to treat you as though you’re insignificant, and I feel like this lab environment is very inclusive and supportive.”

“She is a really good listener,” added Palmeiro. “I had no software or computational background when I came in. I would ask a question, she would give it back, and that helped me a ton. And everybody else in this lab has their own expertise, and we all communicate. We’re a great team that way. Molly brings that atmosphere to the lab and I think that’s why we’re all really successful.”